The Estate - Bevendean History Project

Les Wilson spent his wartime working as a Bevin BoyLes was born in November 1925

and lived at 9 Manton Road when he was a child. He was 14 years old

when war broke out. When he was old enough to serve in the armed forces

he was selected to work in the coal mines due to a shortage of miners,

as many had gone into the armed forces.

I came home on the Saturday and I went down to see him on Sunday. He pulled out an old Church Magazine, tore the back page off and he wrote a letter and said give it to Haynes the Post in Llay, he was a churchwarden, and he got me my digs. That’s how I got to go, I asked to go to Llay and they let me, but then they realised it wasn’t a good idea to let people go where they wanted to, so they stopped it and just put you in a colliery were you were needed.

I was lucky, it was a mechanical colliery with no horses and so therefore there were no rats, no mice and no forage. There was only one wet spot and that didn’t matter, they had stalactites hanging down over a travelling road so it didn’t matter. It was quite a good thing, I was on the lash. There was a great road coming out, it went up and down, a mile long it was. We used to lash full wagons on with the chain at the bottom and at the top do the same with empty ones. I was lashing on wagons that held half a ton of coal which were going up an incline all the time.

I always thought we were only ¾ mile down, we used to get hot down there, it got really hot in the summer we were stripped to the waist and I could drink 6 pints of water on a shift, and I could also knock back some pints at the end of the shift when I was out. The cage we went down in went down vertically in one drop.

Les looked at a photograph of a party to celebrate Victory Europe Day at the end of Lower Bevendean Avenue. That’s Bransby Jones in the picture I don’t remember the party as I was away at the time. I was home for the end of the war the victory in Japan. Bransby Jones was the Vicar of St Andrews Church, he left in 1949.

I came back in 1947 and he was still here. He was the one that got me in the colliery in Wales, as he used to be the vicar of that village. They say he came Brighton in 1935 and went to Portslade first. In September 1934 they had the terrible mining disaster in Dennis (the main shaft) in Gresford Colliery North Wales and Bransby Jones was the vicar of Llay the next door village where I was sent. He was there then and he went to see some of the people of Llay whose relatives were killed in the disaster that was in September 1934.

The miners are still down there, all the men that they never got them out and when I was up there and we were digging the coal we were digging towards the same Dennis shaft.

I left before they got that far, they sunk the pit to a mile deep, I didn’t know that when I was working on the fourteens (coal face area) at the time that we were a mile underground.

Sometime after I left Llay, Marion and I went up to see my mate who worked in the ambulance room and he was on duty on a Sunday. We saw him and he said do you want to go down?

But I said how do you get down and he said there are ways and means, but don’t say anything to anybody. They took Marion and me down. It was a double change then, because as we were going down to the bottom of number 1 pit which was still illuminated, they hadn’t closed it off, and I couldn’t believe it was a mile deep.

I’ve got a little bit of coal that Marion pulled off the coalface there, which is on the shelf. The colliery is gone now. It took 6,000 tons of slurry to fill up the 2 mineshafts. It’s all filled in they’ve got a ring of stones round there with a bit of a garden, that’s all that is left. There is still a lot of good quality coal left under the ground.

Who were the Bevin Boys?

In 1943, as the Second World War raged on and coal supplies dwindled, Britain urgently needed more fuel but many miners had been drafted into the armed forces. In response, a huge group of men was conscripted to the coal mines to meet the demand.

Ernest Bevin decided to introduce a new conscription scheme to create a new workforce, which was dubbed the ‘Bevin Boys’ by the press. Ernest Bevin was a former minister for labour.

The Bevin Boys were chosen out of a hat, class or background was no barrier to being selected to work at the coal face although exemptions were applied to men in highly skilled occupations and those vital for submarine or aircraft crew service.

Every month, for 20 months, Bevin’s secretary drew numbers from his distinctive Homburg hat. If the number drawn matched the last digit of a man’s National Service number, he was sent to the mines.

By the end of the scheme in 1948, 48,000 men from all walks of life had been thrust into the world of coal mining.

The Bevin Boys relied on some resourceful miners’ tricks; they were only issued with a compressed cardboard helmet and a pair of steel-toed boots, and were required to provide their own work clothes by using up their ration coupons.

Miners had flasks of cold tea to quench his thirst in the stifling heat of the mine. When that ran out, they resorted to the miners’ trick of sucking a piece of clean coal to keep his mouth lubricated.

Many of the Bevin Boys were not released from their work until several years after the war ended; continuing after other services had been demobbed. Coal was still required to help rebuild the country.

Llay Main Colliery near Wrexham

Vic Tyler-Jones the Secretary of the Llay Miners’ Heritage Centre got in touch with the website, having seen Les's story on the website, and has provided a short history and some photographs of the coal mine.

The village of Llay is a few miles north of Wrexham in North Wales.

Llay Main became the deepest pit in the country and the largest in Wales, employing over 3,000 men at its peak. Unlike some other collieries it had a reputation of being a happy pit. It had few stoppages because of strikes and prior to nationalisation in 1947, its workers benefitted by having reasonably benevolent mine owners.

The colliery’s two shafts, both 18 feet in diameter were eventually completed in 1921. In 1929 its record year, 1,057,592 tons were produced, but by 1966 as a result of geological problems and reductions in the workforce, the annual output was down to 240,767 tons.

From the start only the most up to date equipment was used at Llay Main. Its steam winding engines by Markhams were considered to be the best in the world. The underground working was illuminated by electric light from the start. The coal was machine cut and filled onto conveyor belts by hand. The tubs were moved along the haulage system by relays of stationary engines powering endless ropes. No ponies were ever used to haul coal.

In 1925 the colliery changed hands and was acquired by the Carlton Mam Colliery Company. They proved to be enlightened employers who fostered a good relationship with the North Wales Miners Association at a time when owners and men at other pits were locked in confrontation. Nationalisation did not make such a great difference to working life at Llay Main but new funds became available in 1952 to be able to extend the bottom of No. l pit to 3,096 feet but the limited take of the colliery meant that most important reserves were exhausted relatively quickly and the workforce was run down after 1959.

The colliery closed on March 11th 1966 and it took six months to fill both shafts with 60,000 tons of mine waste.

Rose Show First Aid Team in 1955.

[from left] Harold Dunnico, Percy Davies [my uncle], Jack Berry, Bill Roberts, Norman Tyler Jones [my father], Stan Rogers, Herbert Henry Jones, Harry Gabriel, Walter Thomas. Harold was rewarded for his labours on this day by winning the raffle for a bottle of whisky.

Also working in the ambulance room at this time was Leslie Crewe, father of my best friend.

Llay Colliery Workshop workers in 1927.

Leslie Crewe is second from the right front row. Leslie was interested in first-aid work and won several competitions. By 1929, he was an ambulance man at Llay Main working under his brother-in-law, Harold Dunnico.

In April 1929, he examined a miner with an old wound to his hand. He advised him to see his doctor immediately. This advice was not heeded and the man subsequently died.

Aerial view of Llay Main Colliery c1955.

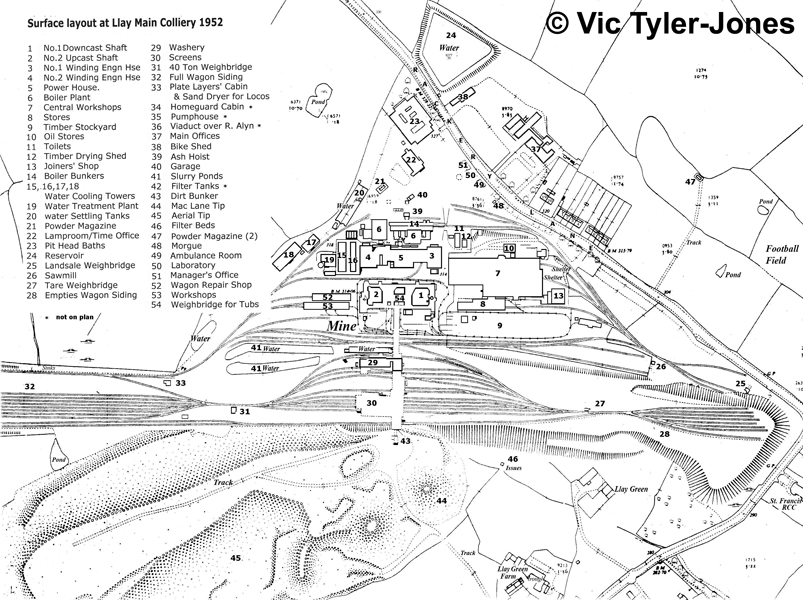

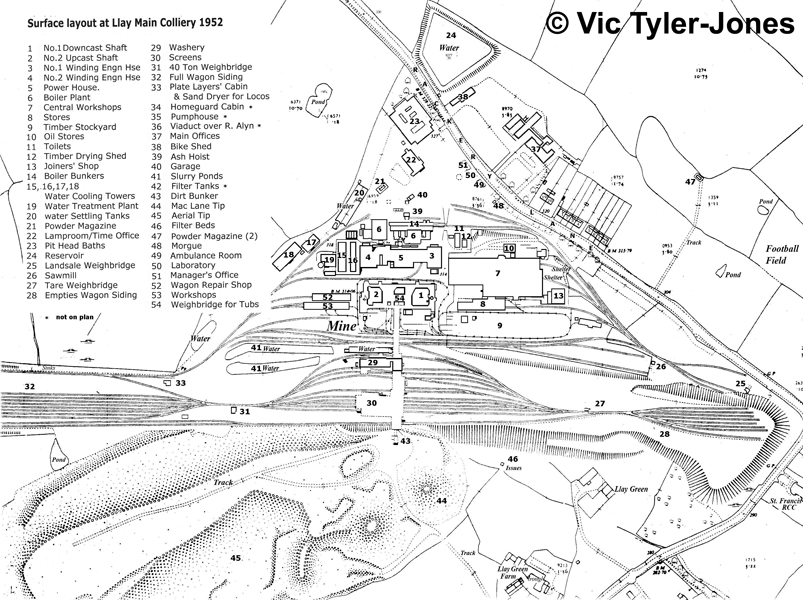

Surface layout of Llay Main Colliery in 1952.

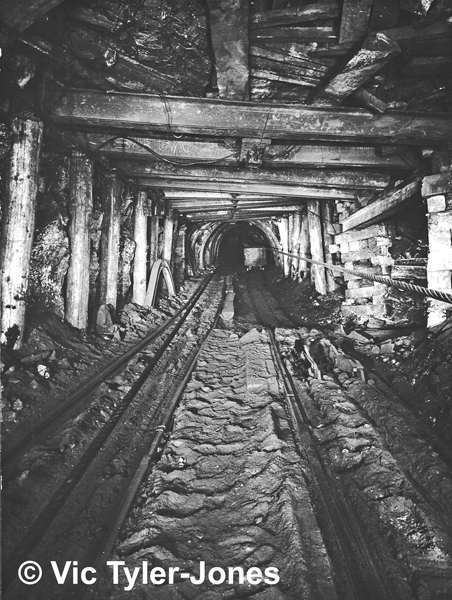

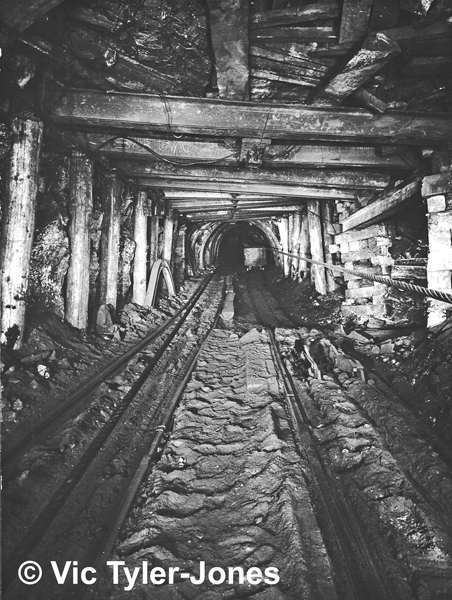

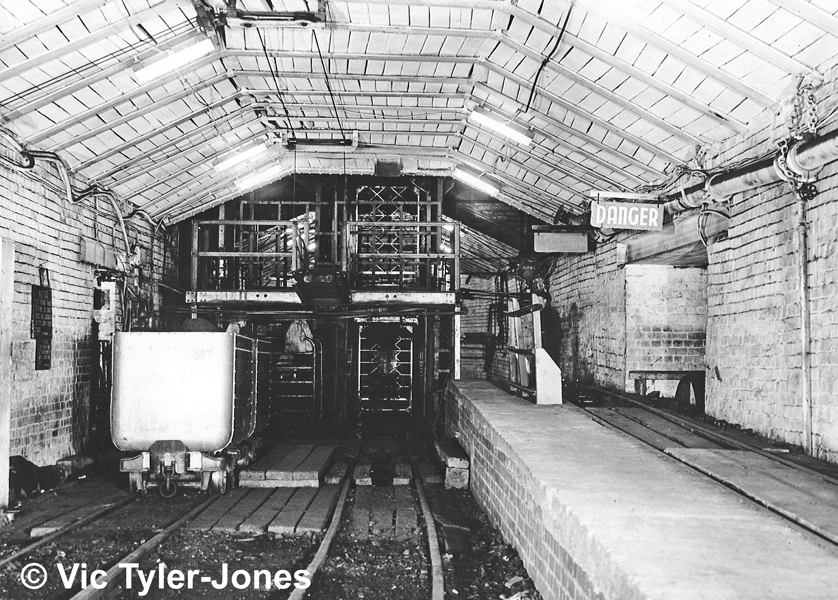

Old haulage road at Llay Main colliery in 1950.

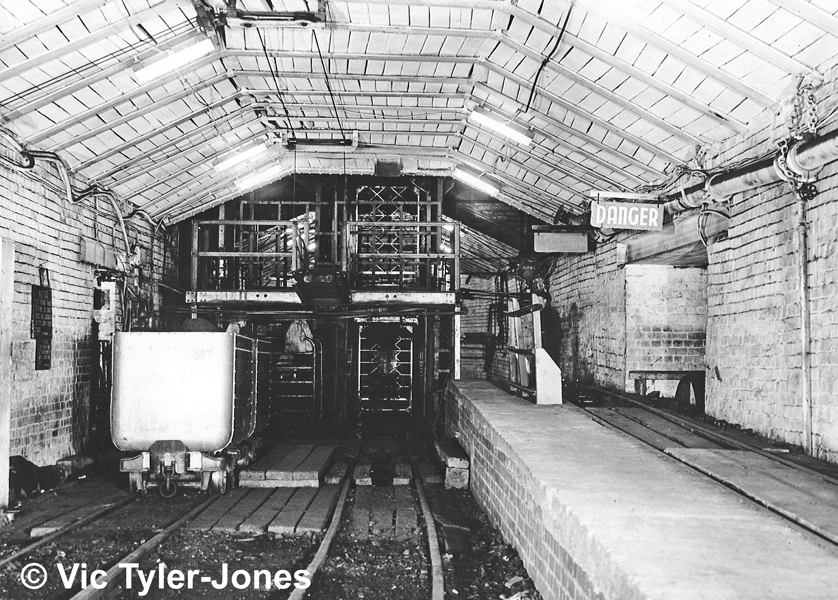

New Pit Bottom at Llay Main Colliery c1954.

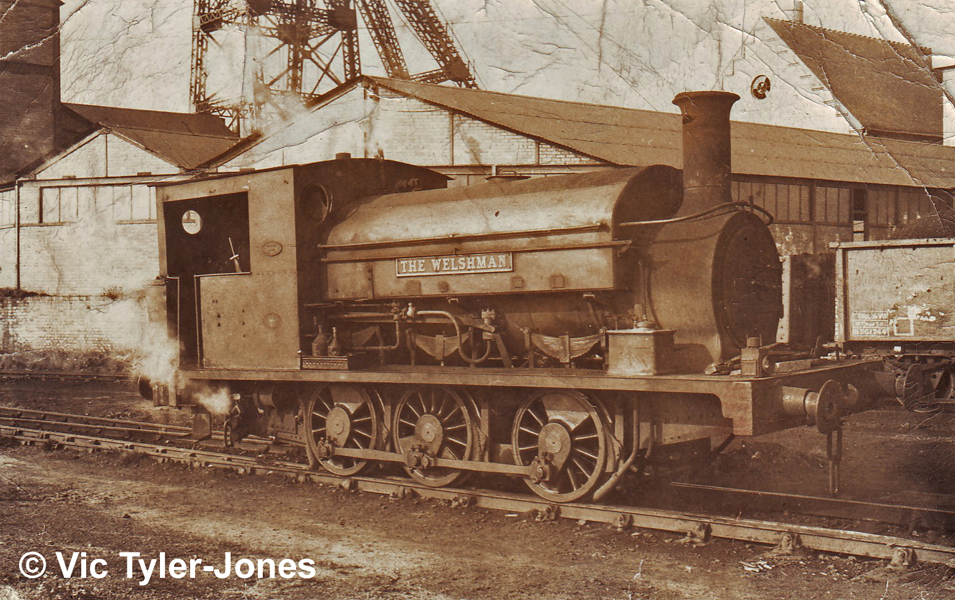

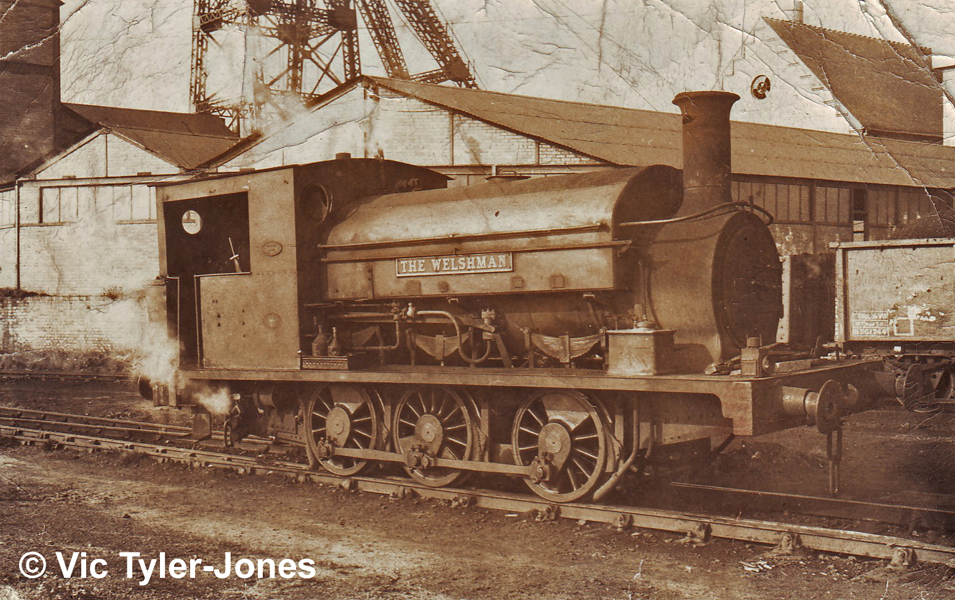

Steam Shunting engine “The Welshman” at Llay Main colliery c1967.

Miners in the Llay Colliery Yard, George Davies on the left with Edwin Jones on the right. Photograph dated 7 March 1964.

More of Les Wilsons memories of his early life in Bevendean can be found here.

|

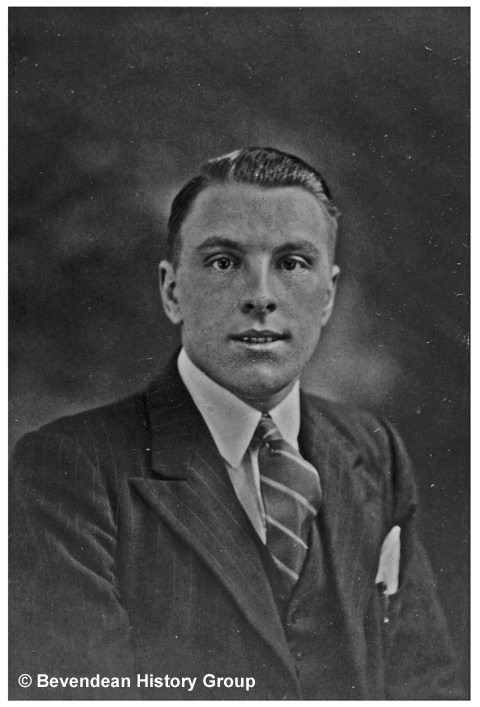

Leslie Wilson photographed at Manchester following his call up to work in the coal mines. Photograph taken in 1944. I got my call up papers on Christmas Eve, although we used to have a post on Christmas Day, and they said I had got to go to Coventry to train and it was a right waste of time. Bransby Jones said to me before I left; see if you can get to Llay mine colliery so I can get you digs. |

I came home on the Saturday and I went down to see him on Sunday. He pulled out an old Church Magazine, tore the back page off and he wrote a letter and said give it to Haynes the Post in Llay, he was a churchwarden, and he got me my digs. That’s how I got to go, I asked to go to Llay and they let me, but then they realised it wasn’t a good idea to let people go where they wanted to, so they stopped it and just put you in a colliery were you were needed.

I was lucky, it was a mechanical colliery with no horses and so therefore there were no rats, no mice and no forage. There was only one wet spot and that didn’t matter, they had stalactites hanging down over a travelling road so it didn’t matter. It was quite a good thing, I was on the lash. There was a great road coming out, it went up and down, a mile long it was. We used to lash full wagons on with the chain at the bottom and at the top do the same with empty ones. I was lashing on wagons that held half a ton of coal which were going up an incline all the time.

I always thought we were only ¾ mile down, we used to get hot down there, it got really hot in the summer we were stripped to the waist and I could drink 6 pints of water on a shift, and I could also knock back some pints at the end of the shift when I was out. The cage we went down in went down vertically in one drop.

Les looked at a photograph of a party to celebrate Victory Europe Day at the end of Lower Bevendean Avenue. That’s Bransby Jones in the picture I don’t remember the party as I was away at the time. I was home for the end of the war the victory in Japan. Bransby Jones was the Vicar of St Andrews Church, he left in 1949.

I came back in 1947 and he was still here. He was the one that got me in the colliery in Wales, as he used to be the vicar of that village. They say he came Brighton in 1935 and went to Portslade first. In September 1934 they had the terrible mining disaster in Dennis (the main shaft) in Gresford Colliery North Wales and Bransby Jones was the vicar of Llay the next door village where I was sent. He was there then and he went to see some of the people of Llay whose relatives were killed in the disaster that was in September 1934.

The miners are still down there, all the men that they never got them out and when I was up there and we were digging the coal we were digging towards the same Dennis shaft.

I left before they got that far, they sunk the pit to a mile deep, I didn’t know that when I was working on the fourteens (coal face area) at the time that we were a mile underground.

Sometime after I left Llay, Marion and I went up to see my mate who worked in the ambulance room and he was on duty on a Sunday. We saw him and he said do you want to go down?

But I said how do you get down and he said there are ways and means, but don’t say anything to anybody. They took Marion and me down. It was a double change then, because as we were going down to the bottom of number 1 pit which was still illuminated, they hadn’t closed it off, and I couldn’t believe it was a mile deep.

I’ve got a little bit of coal that Marion pulled off the coalface there, which is on the shelf. The colliery is gone now. It took 6,000 tons of slurry to fill up the 2 mineshafts. It’s all filled in they’ve got a ring of stones round there with a bit of a garden, that’s all that is left. There is still a lot of good quality coal left under the ground.

Who were the Bevin Boys?

In 1943, as the Second World War raged on and coal supplies dwindled, Britain urgently needed more fuel but many miners had been drafted into the armed forces. In response, a huge group of men was conscripted to the coal mines to meet the demand.

Ernest Bevin decided to introduce a new conscription scheme to create a new workforce, which was dubbed the ‘Bevin Boys’ by the press. Ernest Bevin was a former minister for labour.

The Bevin Boys were chosen out of a hat, class or background was no barrier to being selected to work at the coal face although exemptions were applied to men in highly skilled occupations and those vital for submarine or aircraft crew service.

Every month, for 20 months, Bevin’s secretary drew numbers from his distinctive Homburg hat. If the number drawn matched the last digit of a man’s National Service number, he was sent to the mines.

By the end of the scheme in 1948, 48,000 men from all walks of life had been thrust into the world of coal mining.

The Bevin Boys relied on some resourceful miners’ tricks; they were only issued with a compressed cardboard helmet and a pair of steel-toed boots, and were required to provide their own work clothes by using up their ration coupons.

Miners had flasks of cold tea to quench his thirst in the stifling heat of the mine. When that ran out, they resorted to the miners’ trick of sucking a piece of clean coal to keep his mouth lubricated.

Many of the Bevin Boys were not released from their work until several years after the war ended; continuing after other services had been demobbed. Coal was still required to help rebuild the country.

Llay Main Colliery near Wrexham

Vic Tyler-Jones the Secretary of the Llay Miners’ Heritage Centre got in touch with the website, having seen Les's story on the website, and has provided a short history and some photographs of the coal mine.

The village of Llay is a few miles north of Wrexham in North Wales.

Llay Main became the deepest pit in the country and the largest in Wales, employing over 3,000 men at its peak. Unlike some other collieries it had a reputation of being a happy pit. It had few stoppages because of strikes and prior to nationalisation in 1947, its workers benefitted by having reasonably benevolent mine owners.

The colliery’s two shafts, both 18 feet in diameter were eventually completed in 1921. In 1929 its record year, 1,057,592 tons were produced, but by 1966 as a result of geological problems and reductions in the workforce, the annual output was down to 240,767 tons.

From the start only the most up to date equipment was used at Llay Main. Its steam winding engines by Markhams were considered to be the best in the world. The underground working was illuminated by electric light from the start. The coal was machine cut and filled onto conveyor belts by hand. The tubs were moved along the haulage system by relays of stationary engines powering endless ropes. No ponies were ever used to haul coal.

In 1925 the colliery changed hands and was acquired by the Carlton Mam Colliery Company. They proved to be enlightened employers who fostered a good relationship with the North Wales Miners Association at a time when owners and men at other pits were locked in confrontation. Nationalisation did not make such a great difference to working life at Llay Main but new funds became available in 1952 to be able to extend the bottom of No. l pit to 3,096 feet but the limited take of the colliery meant that most important reserves were exhausted relatively quickly and the workforce was run down after 1959.

The colliery closed on March 11th 1966 and it took six months to fill both shafts with 60,000 tons of mine waste.

Rose Show First Aid Team in 1955.

[from left] Harold Dunnico, Percy Davies [my uncle], Jack Berry, Bill Roberts, Norman Tyler Jones [my father], Stan Rogers, Herbert Henry Jones, Harry Gabriel, Walter Thomas. Harold was rewarded for his labours on this day by winning the raffle for a bottle of whisky.

Also working in the ambulance room at this time was Leslie Crewe, father of my best friend.

Llay Colliery Workshop workers in 1927.

Leslie Crewe is second from the right front row. Leslie was interested in first-aid work and won several competitions. By 1929, he was an ambulance man at Llay Main working under his brother-in-law, Harold Dunnico.

In April 1929, he examined a miner with an old wound to his hand. He advised him to see his doctor immediately. This advice was not heeded and the man subsequently died.

Aerial view of Llay Main Colliery c1955.

Surface layout of Llay Main Colliery in 1952.

Old haulage road at Llay Main colliery in 1950.

New Pit Bottom at Llay Main Colliery c1954.

Steam Shunting engine “The Welshman” at Llay Main colliery c1967.

Miners in the Llay Colliery Yard, George Davies on the left with Edwin Jones on the right. Photograph dated 7 March 1964.

More of Les Wilsons memories of his early life in Bevendean can be found here.

11 September 2019

1940s_War_Time_Stories_001